Tuesday Talk:World Renowned Disability Rights Activist Recounts Struggles and Triumphs in Ongoing Struggle for Rights

Disability rights activist Judith Heumann is a gifted storyteller, the words flowing out of her in a deliberate and determined cadence that commands both attention and respect.

In 1949, Heumann contracted polio at the age of 18 months, a disease that put her in a wheelchair for life. But the disease also turned her into a fierce and unrelenting advocate for the disabled, enabling her to forge a path as one of the world’s foremost activists for disability rights.

During a long and illustrious career in government service, academia, the nonprofit world, and corporate America, the Woodley Park resident has worked tirelessly on behalf of the disabled. In the process, she has played a pivotal role in enacting policies and laws that have eliminated barriers and enhanced the lives of millions of children and adults with disabilities.

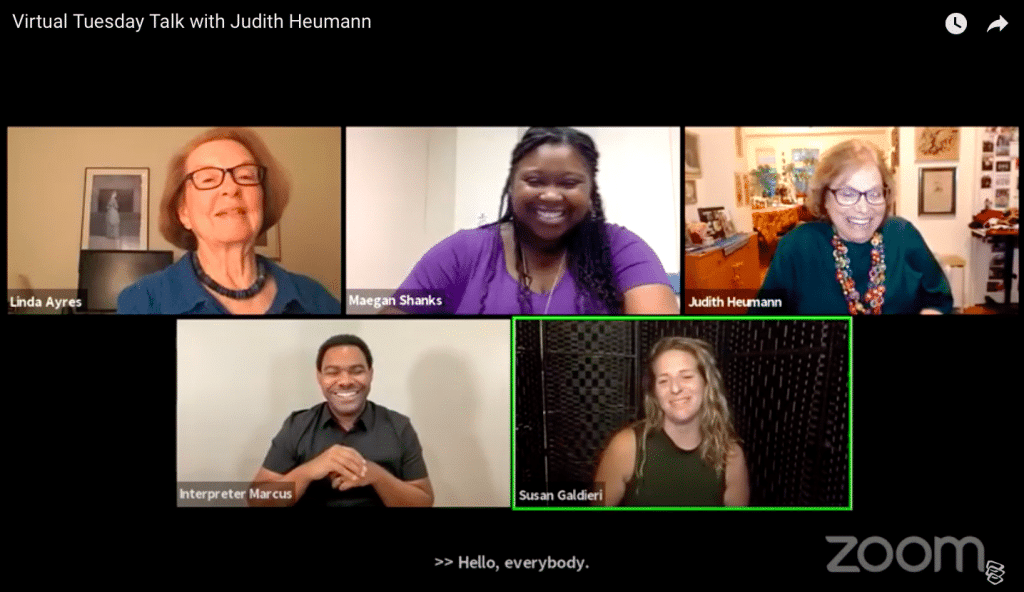

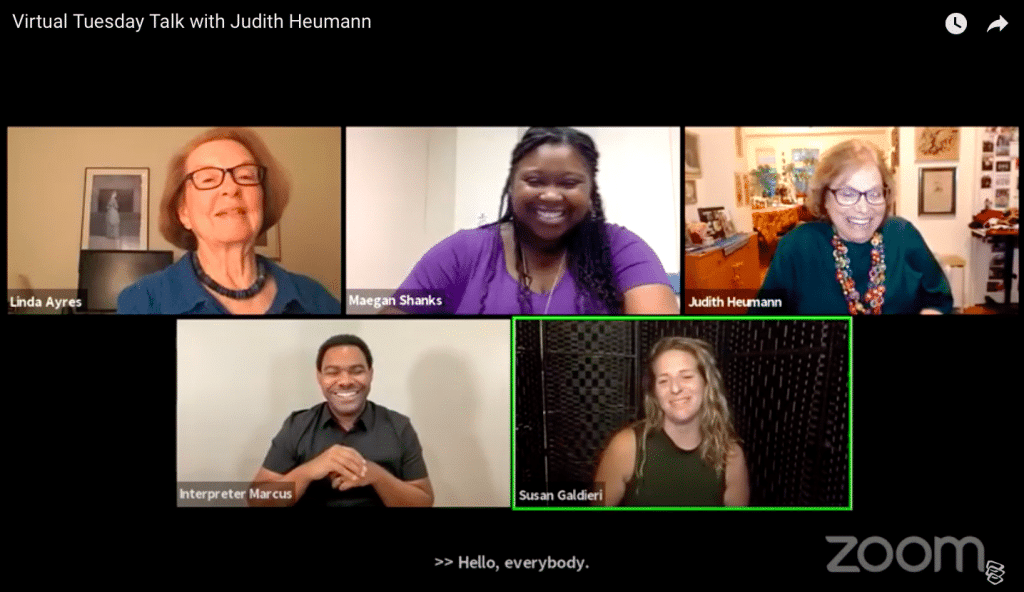

Through it all, Heumann has always been able to rely on her story-telling gifts to paint vivid and compelling pictures of the struggles and hardships she and others endure as disabled people. During the last Tuesday Talk webinar on Sept. 21, Heumann again relied on her remarkable narrating skills to discuss various parts of her life, infusing her words with an uncommon grace and power in recounting her story and, in many ways, the story of countless others living with disabilities.

“I always tell people – whether they have a disability or not – it is really very important for me to tell my story,” said Heumann, who served as the World Bank’s first Advisor on Disability and Development from 2002 to 2006. “I have lots and lots of stories at 73-years-old.”

Maegan Shanks, a deaf woman and disability rights activist who works as the assistant in the MA program in International Development at Gallaudet University, moderated the discussion, speaking through an interpreter, Susan Galdieri. (Shanks is also a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Public Service at American University.)

Being Heumann

Shanks pointed out that Heumann told her life story in a 2020 memoir, Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist, a book co-written with author Kristen Joiner.

Heumann followed her 2020 memoir with another book, also co-written with Joiner, called Rolling Warrior: The Incredible Sometimes Awkward True Story of a Rebel Girl on Wheels That Helped Spark a Revolution, published in July. This book, unlike the 2020 memoir, is geared toward children, though Heumann acknowledged that “it is pretty explicit in the way I describe things.”

“I want the disability community to see the details,” said Heumann, who served as an assistant secretary for the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services at the U.S. Dept. of Education during the Clinton Administration. “But I also think it is very important for nondisabled people of any age to get a better understanding of what it is like to live in the world as a disabled person.”

The book, Heumann said, “represents my life and much of my life is working with other people who experienced discrimination based on disability and other issues.” The book underscores the fact that discrimination against one person – in this case Heumann – affects the lives of so many others.

That point is also made by an Oscar-nominated Netflix documentary called Crimp Camp, which follows the lives of people who attended Camp Jened, a camp for youngsters with disabilities in Hunter, N.Y. Former president Barack Obama and former first lady Michelle Obama funded the documentary through their new production company, Higher Ground Productions.

“We feel very proud the Obamas backed the film with their company, and that Netflix took it on so strongly and that disabled people all over the world are relating to this story,” said Heumann, who attended the camp from the ages of 9 to 18 and is featured in the film, which follows the lives of participants over a 30 to 40 year time frame.

Heumann described the documentary as “an important piece of history,” while expressing the hope that “more disabled people will be involved in looking at different ways of sharing information about our history – not just in the U.S. but also about what is going on around the world.”

Heumann’s own story will also be told in a new Apple original film now under development.

Childhood Struggles

Heumann grew up in Brooklyn, N.Y., and learned early in life that the world was not a welcoming place for the disabled. When her mother tried to register her for kindergarten at the nearby public school, the school principal denied her admission, saying she was a “fire hazard.”

Her parents turned to a Jewish day school, but that school also turned her away even after she met a requirement by learning Hebrew. The local Board of Education eventually agreed to send a teacher to her house for lessons two and a half hours a week.

“I want to emphasize that – two and half hours a week,” Heumann said. “Not a day, but a week.”

It was clear, she said, “that the expectations of what we, and the disabled kids would learn was not the same.”

Heumann did not start attending school until the fourth grade, but it was a school designated for the disabled, requiring her parents to drive an hour and a half each way to school five days a week so she could attend classes.

Heumann and other disabled students attended classes on the first floor while the nondisabled students were taught on the upper floors. They were known as “the kids upstairs,” remembered Heumann.

“The teaching that was going on (on the first floor) was not equivalent to the teaching that was going on in the upper floors of the building,” she said.

Heumann was able to attend high school after her mother and the mothers of other disabled children banded together and convinced the school board to make some of the high schools handicapped accessible.

“There were no laws then – no education laws, no antidiscrimination laws that covered disabled people,” explained Heumann. “So it was really learning by doing, and for those of us who were younger, it was really important we had parents who were advocates.”

Holocaust Survivors

Heumann’s parents were not strangers to hardship and adversity. And they recognized the importance of advocacy.

Heumann’s mother was 12 when she fled Nazi Germany to live with distant relatives in Chicago. Similarly, her father was 14 when he left Nazi Germany to live with distant relatives in the United States. Heumann’s grandparents, great grandparents and other relatives perished in the Holocaust.

Her father eventually enlisted in the Marines, and met Heumann’s mother shortly before he was discharged.

“They wanted to get married and have a family for many reasons,” Heumann noted. “One reason was to help repopulate the Jewish community around the world.”

Heumann inherited a great deal of her parents’ will and perseverance. And she also learned by watching and listening. When her mother, for example, learned that her parents had been murdered in the holocaust “she kept moving forward like millions of other people,” Heumann said.

“People with that type of resilience who continued to move forward, positively influenced our communities,” said Heumann.

The barriers Heumann’s parents experienced in trying to secure a normal education for her made them all stronger, strengthening Heumann’s own convictions in the process.

Fighting Back

Heumann eventually earned a degree from Long Island University and later a graduate degree in public health from The University of California, Berkeley. After graduating from Long Island University in the 1960s, Heumann wanted to teach school, but she could not obtain a teaching license in New York City because the city’s Board of Education said she couldn’t get herself and her students out of the classroom in the event of a fire. In other words, she was again deemed a fire hazard.

A local newspaper ran a headline that said, ‘You Can Be President, Not a Teacher with Polio,’ a reference to Franklin Roosevelt who became the nation’s longest serving president despite having polio. Heumann sued and settled the case without a trial, becoming the first person in a wheelchair to teach in the New York City school system where she taught elementary school for three years.

By the mid 1970s, Heumann was living and working in Berkeley, Calif., serving as the deputy director for the Center for Independent Living. One of Heumann’s proudest and most enduring accomplishments occurred in 1977 when she led a 28-day sit-in at the San Francisco Office of the Dept. of Health, Education and Welfare, HEW, building after HEW Secretary Joseph Califano refused to sign regulations for Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 . The act prohibits federally-funded organizations from discriminating against people with disabilities, making it the first act of its kind.

Other sit-ins took place simultaneously in other HEW buildings in various cities across the country. But the sit-in led by Heumann was the largest – 128 people participated – and the longest, eventually convincing Califano to sign the regulations.

Not surprisingly, Heumann said the disability community learned from the civil rights movement of the 1960s and 70s, borrowing many of its tactics.

“What we were learning by observing and by some people participating in the civil rights movement is you need to fight for your rights,” said Heumann.

Heumann also stressed the importance of cooperation and collaboration, saying, “We needed allies. We needed to work with people who really understood what we were talking about and could support what we were trying to do.”

At the same time, the disability community needed to rely on experts who knew how to make buses, trains and even curbs accessible. The disability community naturally aligned with disabled veterans groups who were trying to enhance accessibility.

Common Interests

During the question and answer part of the Tuesday Talk, one viewer with cerebral palsy asked why there is not greater cooperation between the disability and senior citizen communities.

“Many people do not want to identify as having a disability,” Heumann said in response to the question.

Heumann pointed out, however, that as many people age, they develop disabilities, making them a part of the disabled community.

“At the end of the day, we share common areas of focus,” she said.

In response to another question, Heumann described “disability as a normal part of life.”

“Don’t be afraid of it,” she said. “Embrace it. And learn what you need to do if, in fact, you enter our world. And it is a great world.”