Tuesday Talks: Cleveland Park Library Rebuilding Project That Community Helped Design

The Cleveland Park Library resides deep within the heart and soul of the Cleveland Park community.

In 2016, the Cleveland Park Library underwent a two year $19.7 million restoration (total project cost) that transformed an aging 1950s era building into a traditional but modern 21st century library that stands as one of Cleveland Park’s most iconic and popular landmarks.

During a Tuesday Talk webinar on Jan. 19th the two architects most responsible for the design and creation of the new library – Matthew Bell and Tim Bertschinger of the architectural firm Perkins EastmanDC – discussed some of the specifics of the building restoration. They also explained how the building design fits in seamlessly with the Cleveland Park landscape, and how community involvement played a major role in shaping many of the features of the restored and renovated library. Cleveland Park resident Brian Kelly, director of the architecture program at the University of Maryland, moderated the discussion.

Final Cut

Perkins EastmanDC was one of four architectural firms that made the final list of design/build teams bidding on the contract to rebuild the Cleveland Park Library. Teaming with the Gilbane Building Company, they won the bid largely on the strength of its track record with Gilbane for big projects, its architectural skills as well its knowledge of Cleveland Park, specifically its ability to design a library that would be a unique reflection of the neighborhood’s character.

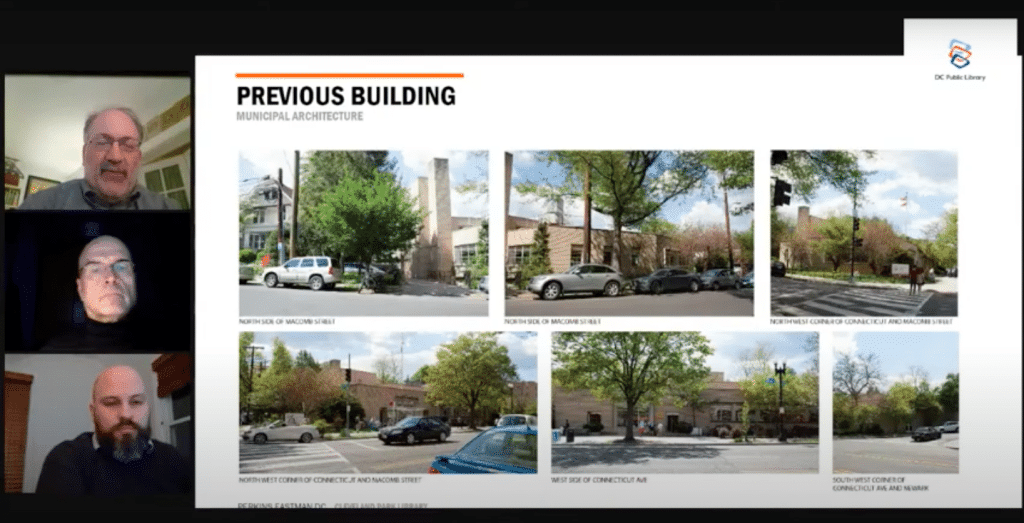

Bell, a principal at Perkins EastmanDC, described the old library as a 1950s version of a large house – an open, free-flowing space, plagued by severe acoustic issues. There was, in fact, no acoustic separation between the various rooms in the old library, allowing noise to bleed from one room to the next. Moreover, the old library lacked an iconic “civic presence,” said Bell.

Although obsolete, Cleveland Park residents loved the old library because of its central location and its fine collection of books and other materials.

Perkins EastmanDC built upon that existing goodwill, creating a structure that reflects the firm’s goal of designing buildings “that really speak to the uniqueness and originality of their settings,” said Bell.

“We try and design buildings and planning efforts that are complements to the sites they sit in so they can be in no other place,” explained Bell.

This is a goal shared by the DC Public Library System and its executive director, Richard Reyes-Gavilan, according to Bell.

Cleveland Park is a unique blend of storefront businesses on Connecticut Avenue tempered by tree-lined streets and nearby parks. The front and sides of the library, for example, house clerestory windows, mimicking the storefront windows on Connecticut Avenue.

Other parts of the building look out over Macomb and Newark Streets as well as the Klingle Valley Trail, thus capturing the neighborhood’s bucolic surroundings.

“I would describe this building as a little bit of a love letter to the neighborhood,” said Bertschinger, a senior architect at Perkins Eastman, who has also taught at the University of Maryland and Catholic University. “People who experience it and walk through it get so many views of the neighborhood and so many different sorts of experiences that it really connects to the neighborhood and not just the site.”

The two architects also sought to build a library with “great spaces where people could meet each other and bump into each other,” said Bertschinger.

For Bertschinger that particular part of the project carried a special significance. As he explained, “I met my wife at the previous library so it was something kind of dear to me in terms of my personal experience.”

Stakeholder Involvement

As architects, Bell and Bertschinger worked directly for the D.C. Public Library System when designing the new library. But they also were accountable to several stakeholders. Cleveland Park, for example, is a DC Historic District, which required the team to obtain approval for their plans from the DC Historic Preservation Review Board as well as the Federal Commission of Fine Arts.

Bell and Bertschinger also worked with the District Department of Transportation as they designed public space around the building.

“We were showing things to various stakeholders,” said Bertschinger. “We were getting a lot of feedback.”

Most of the feedback came from community residents during a series of public meetings – feedback used to arrive at a set of design principles and to propel the project forward.

For example, unlike some communities, Cleveland Park does not have a community center. As a result, Cleveland Park residents wanted a library with plenty of meeting space, a request Bell and Bertschinger honored.

The library’s main meeting room, for example, holds about 200 people, and when divided in two by a partition, 100 people in each room.

The bottom level of the building also contains a large meeting room, holding about 100 people or 50 in each room when divided in half. Ward 3 Councilmember Mary Cheh found extra funds in the DC budget to build the lower level meeting rooms. Without those meeting rooms, the lower level would not be accessible to the public, Bell said.

Cleveland Park residents also cited acoustics as a major concern – a problem solved with the right kind of detailing.

“One of the things we did to challenge ourselves was to put the quietest rooms in the building between the reading rooms and the forums, which is the noisiest space,” said Bertschinger. “We had to look carefully at the detailing of those spaces in order to provide a quiet experience.”

Opposites Attract

The library building is a study in contrasts. The second floor reading room stretches from Macomb to Newark Street, housing a wide-open, bright and airy space that also has a small meeting room in one corner and a series of private, individual reading rooms diagonally across from the small conference room.

Two outside porches, one on Macomb Street and the other on Newark, anchor both ends of the second floor, giving library visitors the option of reading and working outside. Interestingly, the two porches were conceived to relate to the many porches that line the historic houses on Macomb and Newark Streets.

Although widely popular, the two porches presented some security concerns.

Before putting the porches in place, Bell met with Reyes-Gavilan of the DC Public Library System, telling him the porches would be a good option to include, a way of further incorporating the neighborhood’s DNA into the library. He also warned him, however, that someone could steal books by throwing them off the porches to a waiting accomplice on the street.

Without hesitating Reyes-Gavilan said, “We will just have to buy a new book.” In other words, Reyes-Gavilan liked the idea of the porches, allowing them to go forward.

Breaking Down Barriers

Bell and Bertschinger found other ways of making the most out of the library space. In the old library, the children’s section stood near the front desk, but in the new library, the children’s section sits behind the front desk on the first floor adjacent to a small garden with small trees and bushes.

“One of the things we worked very hard with this library is to break down the distinction between inside and outside,” Bertschinger said. “We really wanted to create layers of space that people could enjoy, particularly spaces outside of the library that were accessible. That is something you see in the porches, something you see in the garden.”

Whenever possible the two architects preserved the outside environment. During the presentation, for example, Bertschinger showed a front-view picture of the library from across the street, pointing out that a large and sturdy tree obscures the view of the library.

People sometimes ask Bertschinger why he didn’t have the tree cut down, and Bertschinger responds by saying, “the tree ruins the view of the building, but it certainly doesn’t ruin the experience of being in the place.”

“We really want to find the value of what exists because it is free and already there,” Bertschinger explained. “The more we can leverage that, the more value we can create for communities.”

Bell and Bertschinger were also able to find value in the stairs leading from the first to the second floor by turning the stairs into a winding staircase readily visible – and inviting—from the outside. In a space underneath the stairs on the first floor, the two architects put in a long bench and chairs, creating a reading and working area that resembles a coffee-shop motif.

“I have heard so many refer to the building as the English Muffin of libraries,” said Bertschinger. “There are nooks and crannies and spaces for everybody.”